“What Do Civilians Do?”

I was 19 years old, freshly discharged from the Royal Engineers, and I had absolutely no idea what to do with my life. A decade later, I’d be working as a commercial diver in the North Sea. But at 19? I didn’t even know how to become a commercial diver, or that the job existed.

I remember calling my dad and asking him, genuinely confused: “What do civilians do?”

He laughed and said, “Stuart, you can do whatever you like. The world is your oyster.”

Except I didn’t know what I wanted to do. Or where I was going to go. Outside of the military, I had zero plan.

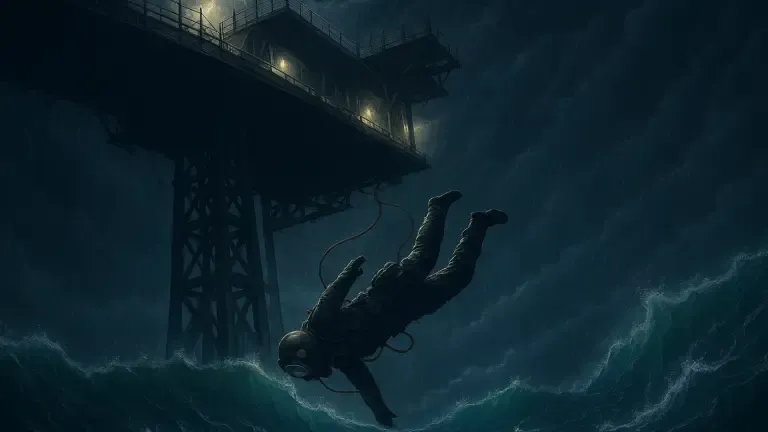

Fast forward a decade, and I’d become a commercial diver working in the North Sea, the Middle East, and West Africa—earning a salary I never imagined possible, doing work most people didn’t know existed.

But the path there? Absolutely chaotic. Dangerous. And full of mistakes that nearly killed me multiple times.

If you’re thinking about becoming a commercial diver UK, this is the real story—not the polished recruitment brochure version. The good, the bad, and the “how the hell did I survive that?”

Growing Up Around Fighter Jets

There’s nothing quite like sitting in a classroom and hearing two Rolls-Royce Spey engines in full afterburner, rumbling through your entire body as a fully loaded Phantom screams overhead.

Even better? Knowing that 20 tons of screaming death is being piloted by your dad.

I grew up on RAF bases. My dad was a fighter pilot. Most of my childhood was in Germany, with stints in the UK and Middle East. My great-grandfather lied about his age and joined the horse-drawn artillery at 15. Both my grandfathers were RAF. Uncles, brothers, cousins—military through and through.

My outlook on life was simple: you joined the squadron your dad was on, you worked in the NAAFI, you were a teacher, or you were German. That was it.

Life on military bases didn’t exactly prepare me for civilian life. So they sent me to boarding school.

I got expelled.

The Pattern: “Stuart’s Intelligent Enough, But…”

Every school report said the same thing:

“Stuart’s intelligent enough to do the work, but he chooses to use his intelligence in other ways.”

Translation: I was a troublemaker who wasn’t interested in academics.

I’d come home dreading the end of term, knowing my parents would read yet another variation of the same disappointment. Coming from a long line of military service, seeing that look on my dad’s face—that was worse than any punishment.

So naturally, I joined the Royal Engineers.

The family tradition continued. Except it didn’t last.

Medical Discharge: The First Pivot

After a short time in the army, I injured myself. Medical discharge. They said: “Take a year off, recuperate, then rejoin.”

But I knew I wasn’t going back.

That phone call to my dad—”What do civilians do?”—that was the moment I realized I had no plan outside the military. None. Zero.

So what did I do? I bummed around for a few years.

Worked at Tesco. Worked in a quarry. Loads of random jobs. Eventually ended up in Edinburgh in my early twenties, partying, DJing, and yes—I even did a stint as a podium dancer.

(That’s probably not a story for here.)

The Intervention: “You Look Terrible”

My dad was working in Oman at the time, teaching weapons and tactics to the Sultan’s Air Force—basically a posh Top Gun in the desert.

He came back to visit and saw the state of me. Pale. Thin. Partying every night. Not exactly thriving.

He said: “We need to do something with you.”

He had a friend in Dubai who ran a diving school. They were looking for staff. The deal:

- Come work for us

- We won’t pay you much

- You’ve done a bit of scuba diving, so we’ll train you properly

- We’ll put you through your advanced scuba, rescue diver, divemaster, and eventually instructor training

I said yes.

Not because I was passionate about diving. Because I had no better options.

Dubai to Khor Fakkan: Learning to Dive (Sort Of)

I moved to Khor Fakkan, a small town about two hours from Dubai over the mountains on the east coast. Beautiful place. Crystal clear water. Perfect for diving.

I learned to teach scuba diving. Got properly certified. Started running courses for tourists.

But here’s the thing about being young, stupid, and newly confident underwater: we had no idea how dangerous we were being.

The Deep Dives That Should Have Killed Us

On days when we didn’t have customers, my mate Gav and I would take the boat out to the shipping lane, find the deepest spot we could, throw the anchor over, and do a “quick deep dive.”

On air. On a single tank. No backup. No safety procedures.

Let me explain why this is insane:

When you dive on regular air (not enriched nitrox or trimix), nitrogen becomes narcotic under pressure. The deeper you go, the more impaired you become. Every 10 meters is roughly like having a drink—at 70 meters, you’re essentially drunk out of your mind.

We were bombing down to 70 meters regularly.

70 Meters on Air: The Dive That Nearly Went Wrong

One day, we took our divemaster trainee Crispin out for a deep dive. He was about 18 at the time.

The plan:

- Crispin stops at 50 meters and waits on the line

- Gav and I bomb down to 70 meters

- We check the bottom, come back up, collect Crispin

- Everyone surfaces safely

What actually happened:

Gav and I got to 70 meters, completely euphoric and off our faces on nitrogen narcosis. I tried to read my dive computer to see how long we had before we needed decompression stops. Eventually worked out we had 2 minutes.

I remember hearing a clicking sound. Thought it was dolphins. Then I realized—it was my regulator, struggling to deliver air at that depth.

I looked at my contents gauge, trying to determine if I had enough air. My impaired brain figured out: “Red is bad, green is good. I’m somewhere in between. Good enough.”

Then I looked up and saw a silhouette floating down toward us, arms and legs flailing.

Crispin had lost all motor control and was sinking.

He’d decided to go from 50 meters to 55 meters—just 5 meters deeper. But that was enough. He hit 55, lost complete control of his arms and legs, and came down like a ragdoll, hitting the seabed in front of us in a big cloud of dust.

Gav and I—completely narced—found this hilarious.

Then I realized: we’re near the no-decompression limit. We grabbed Crispin and took him back to the surface. By 50 meters, he regained control.

Had he done that alone, he’d be dead.

I want to reiterate we we young at the time and diving outside our skill set, looking back on it with trained eyes we were extremely lucky not to have had an accident. I can’t condone this type of risky diving at all now.

Meeting Bob Falcon: The “Commercial Diving” That Wasn’t

Through connections in Dubai, Gav and I met some actual commercial divers earning what seemed like a fortune offshore.

We asked: “How do we get into that?”

They told us about Bob Falcon, who had a diving operation near Abu Dhabi. We drove two hours from Dubai expecting a professional setup.

What we found: A walled yard full of junk, two rabid-looking Dobermans, and a porta-cabin office.

Inside sat Bob—who looked like a cross between Kenny Rogers and a Russian gangster. But he was polite and well-spoken.

We showed up in board shorts, flip-flops, and vests, announcing: “We’re commercial divers, do you have any work?”

He looked at us and knew immediately: we were not commercial divers.

He asked: “Do you have CVs?”

I’d heard of CVs but didn’t really know what one was. “Oh yeah, of course we’ve got CVs. Just don’t have them with us.”

He gave us work anyway.

The Jobs That Should Have Killed Us (Part 2)

Bob hired us for small inshore jobs:

- Harbor swims checking for obstacles

- Installing 12-ton concrete blocks with flanges and Johnson screens

- Swimming through completely enclosed underwater tunnels with no backup

We had:

- A compressor that only filled tanks to 90 bar (should be 200 bar)

- Scuba gear with barely half-full tanks

- No backup diver

- No proper communication

- No one who knew where we were half the time

We should have had:

- Proper dive team with supervisor

- Two divers plus standby diver

- Diving helmets with voice comms

- Umbilicals supplying air from a proper compressor

- Safety harnesses and underwater cameras

Instead: Two idiots in board shorts making it up as we went along.

The Desalination Plant Job: Our Biggest Engineering Project

Bob sent us to a desalination plant called Taweelah. The job: install 12 massive concrete blocks in a staggered formation, each with 36-inch flanges and Johnson screens on top.

These blocks suck seawater up into the desalination plant.

We had no idea what we were doing.

We’d come straight from nightclubs, still drunk, and go to work. We’d go down into the flanges and pipes we’d installed, inflate our BCDs (buoyancy devices), float with the top half of our bodies out of water, and sleep for an hour or two while everyone thought we were working.

One day, a guy in full PPE (hard hat, safety glasses, overalls, boots) woke me up and asked: “Where’s your supervisor? Where’s your dive team?”

I pointed to some bubbles: “He’s over there, tightening up a flange.”

The guy grumbled something about risk assessments and walked off.

We had no idea what a risk assessment was.

Looking back, I don’t know how we didn’t die many times over on that job. But still to this day, you can see that structure from space on Google Earth.

The Underwater Tunnel: Complete Darkness, No Torch

One of the stupidest things we did:

They wanted us to swim up a completely enclosed underwater culvert—basically a tunnel with no air gap at the top—about 300 meters long.

We thought: “Yeah, we can probably make that on a single tank.”

No backup plan. No rescue divers. No torch.

We swam in and it got darker, and darker, and darker. I was holding onto Gav, spinning around, completely disoriented. No sense of up or down.

Then the thought hit me: “What if there’s an obstruction in this pipe?”

If there was grating or shuttering they hadn’t told us about, we’d hit it and die. No way to swim back against the current. No way to get out the way we came in—they’d put the manhole cover back on.

For what felt like an eternity, we just held onto each other in pitch blackness.

Then I saw a tiny pinprick of light. Getting bigger. Blue glow becoming bright green.

We came out into the light like being reborn.

We climbed up the rock dump, sat down, didn’t say a word. Gav got a pack of Marlboro Lights from his jeep, lit two cigarettes, gave me one.

I looked at him: “Well, that wasn’t very good, was it?”

“No mate, let’s not do that again.”

That’s when we decided to get proper training.

South Africa: Learning to Dive Properly

The South African Rand was weak against the pound, so commercial diving training there was relatively cheap compared to the UK.

I scraped together my savings, hit up the Bank of Dad for a loan, and flew to Durban with Gav to attend the Professional Dive Centre.

10-week course:

- Commercial scuba diving (full face masks, proper procedures)

- Surface supply diving (Kirby Morgan helmets, umbilicals, communications)

- Wet bell diving (two divers in a bell, working in pairs)

The training was world-class. We learned:

- Proper safety procedures

- Risk assessments

- Equipment protocols

- Emergency responses

- How things were actually supposed to be done

We came back to Dubai with our Class 2 South African diving certificates, thinking we were ready to take on the commercial diving world.

We had no idea how much we still didn’t know.

First Real Offshore Job: Feeling Like a Fish Out of Water

We met a guy named Mark who worked for a company called SMIT. We walked into his office:

“Hi Mark, we’re baby divers, we’re looking for work.”

He corrected us: “There’s no such thing as baby divers. A diver is just a diver.”

He gave us a job: two months straight offshore in the Middle East.

When I got there, I felt completely out of my depth. Terms and terminology I had no clue about. Everyone seemed to know where they should be. I didn’t.

My First Three Dives Were Disasters

Dive 1: Had to remove a semi-floating subsea hose from a pipeline end manifold (PLEM). Thought I could time it with the swell and lift the hose with my shoulder to remove the last bolt.

Instead, I gouged a massive scrape down the machined flange face—potentially ruining the entire PLEM. The supervisor suggested my first dive might be my last.

Dive 2: Deep dive to 40 meters. As I descended, my breathing got tighter and tighter. The supervisor had forgotten to open my Tescom (air regulator). I started panicking, thinking I couldn’t breathe.

He opened it. I could breathe again. Came out of that dive feeling foolish.

Dive 3: Installing a clamp on a rig leg. Spent 2-3 hours in the water. Got everything buttoned up perfectly. Started swimming back to the vessel.

Then I stopped—couldn’t go any further.

My umbilical was bar-tight between the Kevlar strap and the rig leg. I’d trapped my own lifeline in the clamp I’d just installed.

Had to undo all the work I’d just done to free myself.

Chopper: The Lead Diver Who Saved My Career

After three catastrophic dives, I went to our lead diver, an Australian guy called Chopper:

“Chops, I really think I’ve made a mistake here. I don’t think I’m in the right place.”

His response changed everything:

“Don’t worry about it. It’s your first week. You’re not going to know everything—where everything is, what all the things are. Dig in and you’ll be fine.”

He was right.

The “Bagging” Incident

One day, Chopper told me: “Go grab that bagging and bring it over here.”

I looked for bags. Couldn’t find any. Came back: “Chops, there’s no bags over there.”

“Stu, just go over there. Just bring the bagging over. Stop fucking around.”

I went back, looked again. No bags anywhere. Came back again: “Chopper, there’s no bags. I can’t find anything.”

He literally walked me over, picked up a hose, and said: “Stu mate, THIS is bagging.”

All these terms and terminology were completely new to me.

The Whiskey Test: Proving I Wasn’t a Wanker

A few weeks in, we had some bad weather and were down for a few days. Chopper came to my cabin:

“Stu, I need to ask you a serious question. Have you got any alcohol on board?”

Oh shit. I had a three-liter bottle of J&B whiskey stashed under my mattress.

I thought: Do I lie to him? He’s been so good to me.

“I may have.”

“Show me where it is.”

I pulled out the bottle. He gave me a stern look: “We’re going to have to go see the Offshore Manager in his cabin.”

I thought I was finished. Caught with booze offshore after finally getting my stride.

We got to the OM’s cabin. AC/DC was blaring. I opened the door.

The entire diving crew was inside with drinks in their hands.

Chopper said: “I told you he wasn’t a wanker.”

The Lessons: What I Wish I’d Known

If I could go back and give advice to my younger self starting out, here’s what I’d say:

1. Get Proper Training FIRST

Don’t do what I did—jumping into “commercial diving” work without proper qualifications. We were extraordinarily lucky not to die.

Go to a reputable diving school. Get properly certified. Learn the right way from the start.

2. You WILL Make Mistakes

Theodore Roosevelt said: “The man who makes no mistakes will never make anything.”

Your first offshore job will be humbling. You won’t know all the terms. You’ll make errors. That’s okay. Ask questions. Learn. Grow.

3. Find Good People

Chopper didn’t have to look after me. But he did. He could have let me fail, but instead he encouraged me to dig in.

Find lead divers, supervisors, and companies that support new divers rather than tear them down.

4. The Industry Is Small

Everyone knows everyone. Your reputation follows you. One night of stupidity can follow you for 10 years.

Treat people well. Work hard. Be reliable. That matters more than technical skills.

Want to Learn the Right Path to Commercial Diving?

You don’t have to learn through near-death experiences like I did.

Join the Beyond the Surface community and get:

- Training school comparisons (which ones are worth your money)

- Real guidance from experienced divers

- Honest answers about costs, qualifications, and job prospects

- Support from people on the same journey

👉 Join the free community here – Learn from people who’ve been there.

Final Thoughts

My path to becoming a commercial diver was chaotic, dangerous, and full of mistakes.

But would I change it? Not a chance.

The offshore industry gave me an incredible career, amazing experiences, and friendships that last a lifetime. I’ve worked in places most people will never see, earned money I never imagined possible, and gained skills that opened doors I didn’t know existed.

The key is learning the right way—proper training, good mentors, and companies that prioritize safety over shortcuts.

If I can do it, anyone can. Just maybe do it a bit smarter than I did.

Got questions about getting into commercial diving? Want to share your own story? Drop a comment or join the conversation in our community.